Signatures and ZK proofs: much closer than you think

Credits where credits are due

Real-World Cryptography is an excellent book I’d recommend to any engineer, but especially to engineers working with modern cryptographic primitives or libraries. After reading through it, what’s impressed me most is the explanation of digital signatures in section 7.2. It’s introduced in a way I’ve never seen before. What follows in my own take on it, hope you like it!

Signatures: the usual explanation

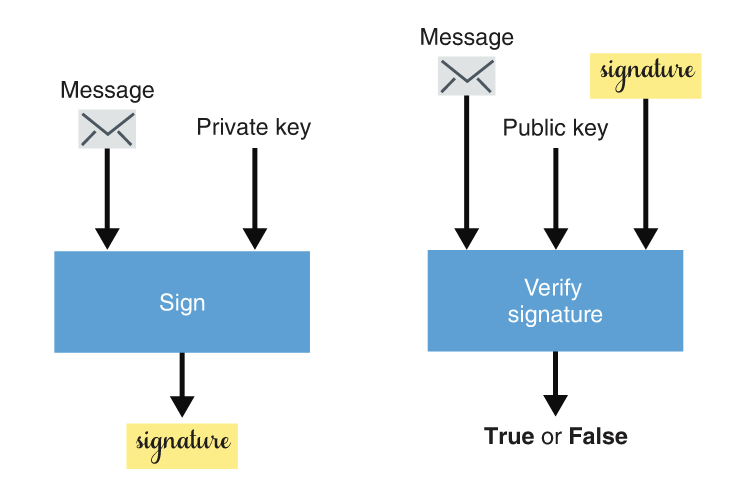

Signatures in cryptography are typically introduced by thinking about the “sign” and “verify” primitives in the abstract (diagram from my copy of the book, p. 130):

- “sign” takes a message and a private key; produces a signature

- “verify” takes a message, a public key, and a signature; produces a binary “true” or “false” result which indicates whether a signature is valid.

Now time for some formulas used to compute or verify signatures.

To sign (`x` is the private key, `M` the message):

- Select a random `k`, then compute `r = g^k`

- Compute `e = H (r || M)`

- Compute `s = k - xe`

- Return `(s, e)` as the signature

And to verify (`p` is the public key):

- Compute `r = g^sp^e`

- Compute `e_v = H(r || M)`

- If `e_v stackrel{?}{=} e`, the signature is valid

…and off you go! The above explanation is “fine” and that’s what we’re used to. But the formulas feel arbitrary, complex, hard to remember, and mysterious.

Signatures can be seen as ZK proofs

When a signature is verified, the verifier obtains proof that the signer knows a number (their private key), without knowing what this number is. Hence signatures can be seen as zero-knowledge proofs. I’ve always thought that this was pretty neat and cool, but ultimately not something very central to the notion of digital signatures. How wrong I was!

ZK proofs are the origin of digital signatures

Digital signatures can be introduced as a direct evolution of zero-knowledge protocols, and more specifically the Schnorr identification protocol.

The solution to demystifying digital signature formulas is to show where they come from! Let’s start from scratch and consider a simple scenario: Alice wants to prove to Bob she knows a number `s` (secret) without revealing it.

A toy ZK proof based on division

Because Alice doesn’t want to reveal her secret we can’t send `s` to Bob directly. Alice needs to send him something (a “proof”) to convince him that she knows `s`. In practice this means we need to define `s` as a number satisfying some kind of constraints. The constraints are public, `s` stays private, and the proof is a way to prove that Alice knows a number which satisfies the constraints.

Let’s make this concrete and simple: we can define `s` as “the number such that `10*x=P`” where `P` is a public number. For a moment, let’s suspend disbelief and pretend that division is a hard problem.

How do we prove to Bob knowledge of `s`? Two techniques are at the core of zero-knowledge proofs:

- The first technique is called hiding: because we assume division is a hard problem, if `x` is a number, `10*x` is called the hidden version of `x`.

- The second technique is called blinding: given some number `x`, I can pick a random value `k`, and `x+k` is called the blinded version of `x`: without knowledge of `x` or `k`, `x+k` is just a random-looking value.

Now we can combine these two techniques to create a proof:

- Alice blinds her secret value `s`: she picks a random `k` and computes `s_{bl\i\nded} = k + s`

- Alice hides the random `k`: she computes `k_{hidden} = 10*k`

- The proof is `(s_{bl\i\nded}, k_{hidden})`

Bob can verify this checking `k_{hidden} + P \stackrel{?}{=} 10 * s_{bl\i\nded}`. This works because:

- `k_{hidden} + P`

- `= 10*k + P` (by definition of `k_{hidden}`)

- `= 10*k + 10*s` (by definition of `P`)

- `= 10 * (k + s)` (because multiplication is distributive)

- `= 10 * s_{bl\i\nded}` (by definition of `s_{bl\i\nded}`)

Pause for a second.

This is it! Aside from a few tweaks I’ll explain below we have all the ideas needed to build modern digital signatures. I find this beautiful, simple, and memorable: one can prove knowledge of a secret by first blinding it with a random value, and sending the blinded secret along with the (hidden) random value.

Tweak #1: prevent random cheating

In our toy protocol we trust Alice to pick a truly random `k`, but what if she doesn’t?

One immediate idea to solve this is to involve Bob and have him provide his own random value (“challenge”) to prevent Alice from cheating. Our protocol becomes an interactive protocol:

- Alice picks a random `k` and hides it: `k_{hidden} = 10*k`

- Bob sends a challenge `c` to Alice

- Alice blinds her secret with both `k` and `c`: `s_{bl\i\nded} = k + c*s`

- The proof is the same: `(s_{bl\i\nded}, k_{hidden})`

To verify, Bob checks `k_{hidden} + c*P stackrel{?}{=} 10 * s_{bl\i\nded}`. Now we’ve solved the problem of bad randomness, but we have introduced another: both Alice and Bob need to be online because our protocol is interactive.

Tweak #2: remove interactivity

To remove interactivity from our protocol we can use what Amos Fiat and Adi Shamir discovered in 1986: the Fiat-Shamir transformation (also known as Fiat-Shamir heuristic, but I find “transformation” clearer).

The idea is simple: because the output of a hash function is both deterministic and unpredictable, we can use this to our advantage: instead of obtaining a random value from Bob, Alice can compute `H(k_{hidden})` and use this as her “challenge”. No need to wait for a message from Bob! And Bob can be convinced that the challenge is random because of the nature of hash functions. Our protocol becomes:

- Alice picks a random `k` and hides it: `k_{hidden} = 10*k`

- Alice computes a challenge with Fiat-Shamir: `c = H(k_{hidden})`

- Alice blinds her secret with both `k` and `c`: `s_{bl\i\nded} = k + c*s`

- The proof is the same: `(s_{bl\i\nded}, k_{hidden})`

To verify Bob checks `k_{hidden} + c*P stackrel{?}{=} 10 * s_{bl\i\nded}` and has to compute `c = H(k_{hidden})` himself. This ensures Alice can’t cheat in the hash computation.

Tweak #3: insert any message you like!

Schnorr realized that anything could be included in the hash input used to generate the challenge. Indeed if `c = H(k_{hidden})` is an unpredictable challenge, so is `c = H(k_{hidden} || “hello”)` (where `||` represents concatenation).

As a result Alice can include any message she likes! This is how signatures emerge from proofs of knowledge: a proof of knowledge of `s` with a chosen message `M` becomes “a signature of `M` with `s`”. Here’s our protocol with this tweak:

- Alice picks a random `k` and hides it: `k_{hidden} = 10*k`

- Alice computes a challenge with Fiat-Shamir and inserts a message of her choice: `c = H(k_{hidden} || M)`

- Alice blinds her secret with both `k` and `c`: `s_{bl\i\nded} = k + c*s`

- The proof is the same: `(s_{bl\i\nded}, k_{hidden})`

Then Bob computes `c = H(k_{hidden} || M)` and checks `k_{hidden} + c*P stackrel{?}{=} 10 * s_{bl\i\nded}`. We now have a real Schnorr signature scheme! The final tweak is an obvious one: let’s pick a truly hard problem instead of division.

Tweak #4: pick a harder problem

Time to un-suspend disbelief: our toy protocol above isn’t secure because it’s not hard to invert multiplication by 10. Anyone can retrieve `s` given `P` with a division operation: `s = P/10`.

Digital signatures use exponentiation modulo a large prime: `x -> g^x mod N`. The inverse is called the discrete logarithm: `x -> log_{g}(x) mod N`, and is assumed to be hard (you read this right: we still don’t know for sure!).

Alice now proves to Bob that she knows `s` when `s` is defined as “the number such that `g^s` = `P`”, where `P` is public (Alice’s “public key”). In other words: a proof of knowledge of discrete logarithm rather than a proof of knowledge of division previously.

Surprisingly this tweak doesn’t change how signatures are produced much. It only affects how we “hide” our random `k` in the first step:

- Alice picks a random `k` and hides it: `k_{hidden} = g^k`

- Alice computes a challenge with Fiat-Shamir and inserts a message of her choice: `c = H(k_{hidden} || M)`

- Alice blinds her secret with both `k` and `c`: `s_{bl\i\nded} = k + c*s`

- The proof is: `(s_{bl\i\nded}, k_{hidden})`

Verification changes because multiplication is replaced by exponentiation (notations are harder to read and reason about, which is why I’ve stuck to simple multiplication/division until now):

- Bob computes `c = H(k_{hidden} || M)`

- Bob checks `k_{hidden}*P^c stackrel{?}{=} g^{s_{bl\i\nded}}`

Now we’ve arrived at the real Schnorr signature formula! Typically `k_{hidden}` is called `r`, the challenge `c` is called `e`, and `s_{bl\i\nded}` is simply `s`. Check this out on wikipedia.

Conclusion

We’ve seen the usual explanation for digital signatures and why it sucks: the formulas feel arbitrary and hard to remember. Inspired by section 7.2 of Real-World Cryptography I’ve started from a very simple toy zero-knowledge protocol and applied successive tweaks to arrive at real-world Schnorr signatures:

- The toy protocol relies on two general tricks: hiding and blinding.

- We solve for dishonest random numbers by introducing an interactive challenge.

- We remove the interactivity by leveraging the Fiat-Shamir transformation.

- We include messages in non-interactive challenges: this is the birth of signatures!

- Finally we switch from trivial to hard problem (division to discrete logarithm)

With that I hope the formula behind Schnorr signatures feels elegant, memorable, and less arbitrary!

P.S: It should also become obvious why verifying a signature without hashing the message is a cardinal sin in cryptography. Without this step Bob gives up his involvement in the protocol, Alice can cheat by using non-random nonces, and the security of the scheme falls apart: Alice can prove knowledge of her secret key (produce signatures) without actual ownership of it!